Quick Links

Academic Context

This post reviews and delivers the academic context around the foundations of the Texas Entrepreneurship Report. It will also aim to corroborate its conjectural findings with historic and current research efforts on Texas entrepreneurship.

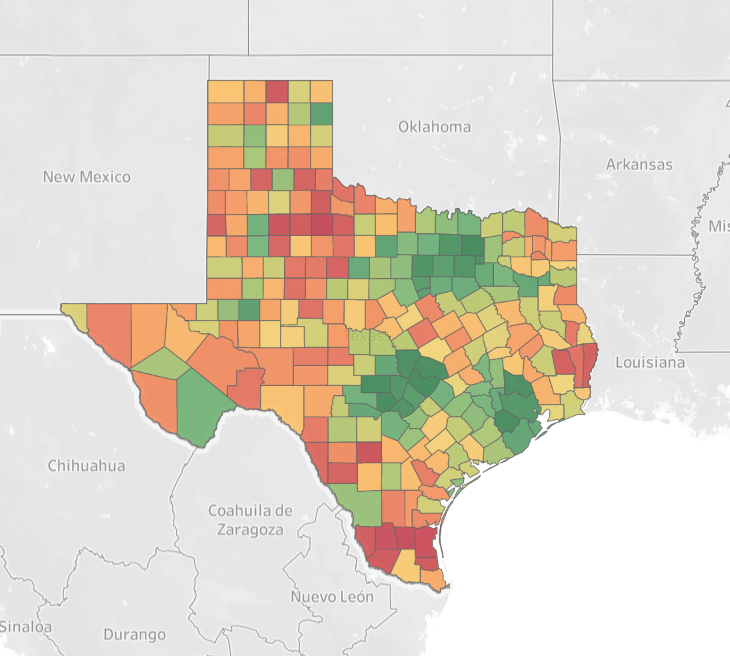

The Entrepreneurship Score computed by the dashboard bases itself on three (3) metrics: # of patents awarded, # of small business loans, and # of new companies. To standardize these metrics across counties, they were divided by each county’s population to compute per capita measures.

While these measures seem reasonable, it is natural to wonder:

How is entrepreneurship usually measured?

In 2016 Measuring Entrepreneurial Businesses1, Guzman and Stern used new business creation as a central metric. They also tapped patent activity to distinguish whether businesses were offering new advancements, or instead just setting up a local instance of a routine business.

The Kauffman Indicators of Entrepreneurship2 track 3 data series: new business creation, early-stage business development, and private sector jobs. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor3 (GEM) takes this game to another level, measuring Entrepreneurial Activity with early-stage businesses, entrepreneurial employee activity (when a new department or product is created from within an established company), and social entrepreneurship.

Texas entrepreneurship research

Our quantitative research of Texas entrepreneurship did not account for many other ways of surveying local conditions, including field research. Therefore, it might be helpful to consider how other groups approached Texas entrepreneurship in the past.

Our report’s findings touch on the history of economic conditions of various Texas regions. They also provide possible explanations for regional economic trends using socioeconomic correlations.

Butler, a past member of the IC2 Institute at UT Austin, argues4 that entrepreneurship can become as significant a economic driver for rural Texas in modern times as the Homestead Act was in the 20th century.x

In 1983, Kosmetzky and Smilor reviewed4 Texas' progress from the start of the 20th century until the 1970s, and proposed entrepreneurship as the vehicle for explosive growth. They proposed federal and state interventions, such as increased Defense R&D speding and State seed funding to increase Texan competitiveness. Their centralization hopes actualized, as since 1990 our analysis indicated strong entrepeneurship clusters in all large cities of Texas.

Pisani and Yoskowitz studied informal entreprneurship in the border region, finding5 that home gardening was the culmination of determination to lead a good life when basic infrastructure and human capital are in despair.

- Kyrylo

-

“Nowcasting and Placecasting Entrepreneurial Quality and Performance” By Jorge Guzman, Scott Stern, 2016. Chapter: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c13493 ↩︎

-

“Kauffman Indicators”, https://indicators.kauffman.org/about-the-kauffman-indicators ↩︎

-

“Global Entrepreneurship Monitor”, https://www.gemconsortium.org/about/gem/ ↩︎

-

“Transforming Texas and the Nation: Productivity Through Entrepreneurship and Risk-taking”, Kosmetzky and Smilor, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/1f440135-c430-46e1-bd2d-66da6603957e ↩︎

-

“Opportunity Knocks: Entrepreneurship, informality and home gardening in South Texas”, Pisani and Yoskowitz, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08865655.2006.9695660 ↩︎